Abstract

The re-creation of society involves the bottom-up-emergence of social information

and the top-down-emergence of individual information. Social self-organisation

in a broad sense refers to the re-creation of society, in a narrower sense it

takes aspects of participation in the processes of constituting social information

into account.

1

Introduction

Traditionally,

information has been conceived as a thing that is transmitted from a sender

to a receiver. It has been fetishized and reduced to technological aspects [Fuchs

and Hofkirchner, 1999]. By combining the notions of information and self-organisation

and establishing a Unified Theory of Information [Fuchs and Hofkirchner, 2001],

such shortcomings could be avoided. Such a theory makes use of a dialectic of

generality and speciality, i.e. general aspects of information are defined that

can be found in all types of systems and emergent aspects of information that

are specific for each special type of system. Such an approach sees information

as a category that can be found in various types of systems- in physical, chemical,

biological, social, ecological, technological etc. ones. Each time a system

organises itself, information is produced; hence all self-organising systems

are information-generating systems.Some work has been done in researching

the relationship of information and self-organisation [Ebeling and Feistel,

1992; Ebeling, 1993; Ebeling, Freund, Schweitzer 1998; Goonatilake, 1991; Haken,

1988; Küppers, 1986; Mainzer, 1998], but although some of these approaches consider

information as an emergent and evolutionary quality of complex, evolutionary

systems, neither one has described the transformations information undergoes

as well as the new qualities information shows when evolutionary steps from

organisational levels to higher levels are considered. The existing approaches

are very scattered and only cover aspects that refer to single types of systems.

A unified concept does not yet exist. In this paper I want to point out some

aspects of information and self-organisation in social systems which constitute

the upper level of an evolutionary hierarchy of self-organising systems and

are the most complex systems we know today.

Robert

Artigiani [1999] argues that society stores information about itself, the

world and the individuals. He sees information in analogy to Shannon as a

measure of the reduction of uncertainty in the world. “Social information

measures the degree to which uncertainty about the environment in which a

society is embedded is reduced. Social information is stored in all sorts

of forms, but rituals, roles, customs, and myths are, perhaps, the most obvious.

[…] Rituals, roles, customs, and myths reduce collective uncertainity about

the external environment by storing information about solutions to past environmental

situations” [Artigiani, 1999: 484]. Artigiani says that information is stored

in VEMs (values, ethics, morals) that code information qualitatively in the

sense of “good” and “bad”. Shannon’s measure of information is a technological

category. If such a category is simply transferred to the social sciences,

false inferences, shortcomings and a mechanistic view of society must be the

outcome. Artigiani argues that society is becoming more and more predictable

and stabile during the course of evolution. But the theories of complexity

show us, that society is a complex and antagonistic system and that only some

very limited aspects can be predicted. Artigiani does not critically assess

existing types of social information and their repressive and exclusive character

[Fuchs, 2001], in an idealistic manner he does not cover aspects of material

production. Nonetheless Artigiani’s work is important because he points out

cultural aspects of social information.

2

Individual and Social Information

In

social systems individual values, norms, conclusions, rules, opinions, ideas

and believes can be seen as individual information. Individual information

does not have a static character, it changes dynamically. E.g. individual

opinions and values change permanently because of new experiences. This does

not mean that individual information is necessarily always unstable and that

e.g. the reflection of ideologies in individual information does not exist.

Instead, new experiences enhance and consolidate already existing opinions,

but can also radically change them. Hence it can be said that individual information

as a lower level of information in social systems has an unstable character.

When we come to higher levels (as we will see with social information that

is constituted in social relationships) the complexity as well as the stability

of information increases. The constitution and differentiation of individual

information has been described somewhere else [Fuchs and Hofkirchner, 1999,

2001; Fuchs, 2001; Fuchs et al., 2001].

Wolfgang Hofkirchner [2000] has pointed out

that in the process of constitution and differentiation of individual information

the signs data, knowledge and individual wisdom can be identified. On the basis

of signals, data is gathered (perceiving). This data is the starting point for

gaining knowledge (interpreting) which is necessary for acquiring wisdom (evaluation).In

a social system, social self-organisation (I) in a very broad sense refers to

the re-creation of such a system. Re-creation denotes that individuals that

are parts of a social system permanently change their environment. This enables

the social system to change, maintain, adapt and reproduce itself. It can re-create

itself permanently due to the individual actions that are related and co-ordinated

socially. A sign can be seen as the product of an information process. An information

process occurs whenever a system organises itself, that is, whenever a novel

system emerges or qualitative novelty emerges in the structure, state or behaviour

of a given system. In such a case information is produced. It is embodied in

the system and may then be called sign.Re-creative, i.e. social systems,

reproduce themselves by creating social information: The word "social"

in the term social information denotes that such a form of information is constituted

in the course of social relationships of several individuals. A social relationship

is established if an interrelated reference exists between (at least) two actors.

Social acting is orientated on meaningful actions of other actors. Social actions

are a necessary condition for a social relationship, but not a sufficient one

because social acting does not necessarily require an interrelated reference

of actors: One actor can refer to the actions of another one without the latter

referring to the first.We consider the scientific-technological infrastructure

(part of the techno-sphere),

the system of life-support elements (part of the eco-sphere)

in the natural environment

and all that in addition makes sense in a society, that is, economic resources,

political decisions and the body of cultural norms and values, laws and rules

(part of the socio-sphere) as social information [see also Fuchs, 2001; Fuchs et al., 2001; Fuchs and Hofkirchner, 2000,

2001; Fuchs 2002). We have no space to cover information production in the techno-

and eco-sphere here [for further details see Fuchs et al., 2001], so we will

concentrate on the socio-sphere where economical, political and cultural information

(which are all subtypes of social information, we do not cover technological

and ecological information here) are constituted in the course of social actions. Such a concept of information covers aspects of mental as well as

of material production. The involved individuals must have a common view of

reality which is the basis for their social interactions and social actions.

They are elements of a social system. As a result of their interactions in social

systems, social information emerges as a macroscopic structure. The interactions

are mediated by acts of communication, the individuals act in such a way that

associations and actions of other individuals are triggered. The individuals

co-ordinate their actions in such a manner that they can commonly produce a

social information structure.In

his theory of structuration, Anthony Giddens [1997] terms rules and resources

as structures that are medium and result of social actions [Giddens, 1997: 77).

He says that social structures are an expression of domination and power and

that rules always relate to the constitution of sense and the sanctioning of

social actions (p. 70). Giddens further distinguishes between allocative and

authoritative resources. The former relate to abilities that make the domination

over objects, goods and material phenomena possible. The latter concern the

generation of domination over individuals and actors (p. 86). Concerning the

institutions of society, Giddens says that symbolic orders, forms of discourse

and legal institutions are concerned with the constitution of rules, political

institutions deal with authoritative resources and economical institutions are

concerned with allocative resources.Giddens says that domination

and power are phenomena that are characteristic for all types of society. He

stresses that domination cannot be overcome as is often imagined by socialist

theories (p. 84f). Giddens does not give an explicit definition of domination

and power and he naturalises relationships of domination and exploitation. His

theory affirms capitalist and class society. He does not even consider societies

without classes and domination as possibilities of social evolution. Power

can be seen as the disposition of means in order to influence processes and

decisions in ones own sense. Domination refers to the disposition of means of

coercion in order to influence others, processes or decisions. Domination always

includes sanctions, repression and threats of violence. So power really is constitutive

of all types of societies and the question is not whether one can abolish power,

it is how power shall be distributed. Today, power in the areas of economics,

politics and culture is distributed asymmetrically, but a wise society that

would be socially and ecologically sustainable would have to progress towards

a symmetrical distribution of power. Domination in contrast to power can not

be distributed, but it can be overcome. Our own model of society

is a general one that does not only cover modern capitalist societies and that

tries to avoid a naturalisation of relationships of domination/exploitation/class.

Hence we do not speak of rules because they – as Giddens says – always include

sanctions and domination, but we have the more general concept of decisions.

Decisions are made in each type of society during the course of social relationships

and by communicative actions, whereas rules that involve sanctions which are

executed if they are not followed are only characteristic for societies that

are constituted by relationships of domination. In our modern societies, decisions

take on the form of formal laws and informal habits. Giddens also

does not speak of culture as a subsystem of society where social values and

norms are being constituted. For Giddens, culture does not seem to be an important

category of society. In his main work [The Constitution of Society; Giddens,

1997] which covers more than 450 pages, he only once writes about culture

as it is seen by Freud, Marcuse and Elias [Giddens, 1997: 296f]. All

of this shows that models of society should have a dialectical character: On

one level they must be general enough in order to explain all possible types

of societies, on the other there must be specific levels that help to explain

specific formations of society (such as capitalism) and different phases of

these formations. The model outlined here is a general one. It is possible to

go one step further in order to describe our modern society as a capitalist

one. On a third level, concrete modes of development can be distinguished which

describe the different phases of capitalism that we have been experiencing.

Currently we live in a postfordist, neoliberal and information-societal mode

of development of capitalism [see Fuchs, 2001]. Giddens clearly fails to consider

this dialectic of generality and speciality. He takes societies that are imprinted

by relationships of domination, exploitation and class as a general standard

of society. This is a typical western and imperialistic view that naturalises

modern capitalistic society and generalises it as the essence of society. Giddens’

theory hence can be characterised as essentialistic and sociological imperialism.

In order to avoid such shortcomings a dialectical methodology should be followed

in constructing sociological theories and models.

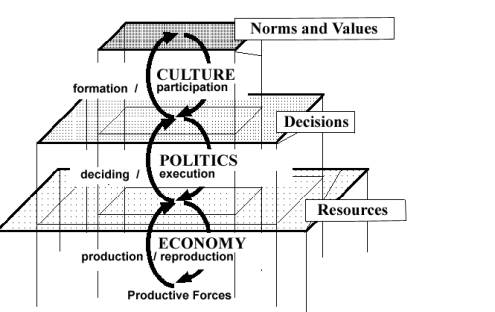

Figure

1: The constitution of social information [see

also Fuchs, 2002; Fuchs et al., 2001]

In all

social systems and formations of society there are three manifestations of information:

resources, decisions and norms/values. They store information about past social

actions and simplify future social situations because by referring to social

information the basics of acting socially do not have to be formed in each such

situation. Social information can be seen as a durable foundation of social

actions which nonetheless changes dynamically. It

can be found in all subsystems of society – the economy, politics and culture.

Economic processes have to do with the production, distribution and allocation

of use values and resources. The foundation of each economic process is formed

by the productive forces. The latter can be seen as a system of living labour

force and factors that influence labour. Living labour and its factors form

a relationship that changes historically and is dependent on a concrete formation

of society (such as capitalism).The

influencing factors can be – as suggested by Marx – summed up as subjective

ones (physical ability, qualification, knowledge, abilities, experience), objective

ones (technology, science, amount and efficacy of the means of production, co-operation,

means of production, forms of the division of labour, methods of organisation)

and natural ones. These forces can only be viewed in their relationship to living

labour. The system of productive forces can never be reduced to these forces,

the system is only possible in combination with human labour. This system is

more than the sum of its parts, it is an integrated whole that lies at the foundation

of economic processes.Resources

can be seen as social information on the economic level. The economy includes

a double process of production and reproduction: Material resources that are

necessary for society to exist (e.g. different products) are produced by making

use of the system of productive forces on the one side. On the other hand, resources

are also applied in order to reproduce the system of productive forces. Reproduction

encloses e.g. the reproduction of living labour force (consumption, spare time

etc.) and scientific progress.Production

and reproduction can be seen as the material basics of each type of society.

Such a Materialistic view is not a reductive and vulgar one, if one considers

that the political and economical superstructures depend on economic processes,

but nevertheless work in relative autonomous ways and also influence economics

in processes of downward causation. They are related in a dialectical way because

economic influences on culture and politics can cause the emergence of new cultural

and political phenomena and political and cultural influences on economics can

cause the emergence of new economical phenomena.Politics

deals with decisions which refer to the way resources are being used and how

they are distributed. Politics refers to decisions which influence the ways

of life and the habits of the members of society. The latter always relate to

material resources because culture and habitus as social phenomena always deal

with the usage and distribution of material resources.

The decisions which are being reached in a social and communicative way in the

area of politics, are also a type of social information. Politics encloses a

double process of deciding and executing: In relation to available resources,

decisions are being reached in order to organise the functioning of society.

These decisions either take on coded or non-coded forms. Once they are reached,

the next step is executing them. And executing decisions always means

that resources of society are applied in a specific form. Culture

can be seen as the subsystem of society in which ideas, views, social norms

and social values are being formed within the framework of habits, ways of life,

traditions and social practices. The emerging social norms and values are a

type of social information that comes into existence in the area of culture.

Culture encloses a double process of formation and participation. On the one

hand, social norms and values are constituted and differentiated in relation

to already reached decisions. On the other hand, social norms and values are

a foundation for further decisions and the differentiation of already existing

ones. The type of participation determines if, how and to which degree individual

actors and social groups can influence decisions which effect them. Neither

culture, nor politics are determined by economic processes. Each subsystem has

a relative autonomy, nonetheless in modern capitalist societies economic processes

have dominating effects. For the area of culture we follow views that stand

in the tradition of the Cultural Materialism of Raymond Williams [1961] that

has had tremendous influence on the whole area of Cultural Studies. Williams

argues that culture includes the “whole way of life” [Williams, 1961: 122],

including collective ideas, institutions, descriptions by which society reflects

experiences and makes sense of them, ways and traditions of acting and thinking

and intentions that result from it. Williams further stresses that culture involves

the formation of values as social categories. Edward P. Thompson [1961] took

up Williams’ theory of culture and added the idea that the whole way of life

and experience is influenced by class struggles and social conflicts. All

of this shows that culture is neither independent from political and economic

processes, nor can it be reduced to these areas, nor is it determined by them.

Already Antonio Gramsci stressed that superstructures cannot be reduced to the

economic base and that culture involves the “creation of (new) world-outlooks”

and morals of life [Gramsci, 1980]. Materialistic theory that deals with culture

has always stressed cultural information, its relative autonomy and its relationship

to socio-economic processes, only vulgar forms of Materialism reduce culture

or politics to economics. Culture as the top level in our hierarchy depends

upon economics and politics, it forms an integral whole of social life that

includes the areas and ways of life we find in the areas of idealistic and material

reproduction [Marcuse, 1937: 62]. Political and economic institutions and relationships

have their own form of culture, and culture can only be thought in relationship

with political and economic processes, although it has a certain degree of autonomy.

The complex interplay of culture and politics is the area where hegemony – as

a specific phenomenon of societies that are constituted by relationships of

domination – is formed. Figure

1 shows the processes of constitution and differentiation of social information.

These processes form an integrated whole which encompasses the three subsystems

of society (economy, politics and culture) and the manifestations of social

information in these areas. Resources can also

be termed economic information, decisions can be seen as political information

and social norms/values as cultural information. Together we refer to them as

social information. The productive forces form the base for the emergence of

economic information which itself forms the base for the emergence of political

and cultural information. The whole social system encompasses three cycles of

self-organisation which result in the emergence of social information on an

economic, a political as well as a cultural level. On the one hand, economical

information influences the emergence of political and cultural information and

political information influences the emergence of cultural information in processes

of bottom-up-emergence. On the other hand, cultural information influences the

emergence of political and economical information and political information

influences the emergence of economical information in processes of top-down-emergence.

Nonetheless, economics and economical information form the base of each type

of society. They dominate, but never determine the various social processes

and the formation and differentiation of social information.

Economics,

politics and culture are interrelated and influence each other. The causality

that applies to these relationships is not a mechanistic and deterministic

one. An effect can not be reduced to a single cause. In society, we find a

multidimensional and complex type of causality: One cause can have many effects,

and one effect an ensemble of many causes. Society is a system with a high

degree of complexity, hence causes and effects cannot be related to each other

bijectively. One sub-system of the society does not determine the actions,

structures and processes in other sub-systems. Society can not be reduced

to simple mechanistic models of base and superstructures. But, at least in

capitalist society, the economy dominates the other sub-systems; i.e., economics

do not determine social actions and development of politics and culture, but

it influences these sub-systems in such a manner that the latter are coined

by the economical logic of capitalism that depends on the accumulation of

capital and the production of commodities. But such influences can never be

totally, as suggested by some types of Structuralist Marxism or the definition

of Historical Materialism given by Frederick Engels [1884]. Such arguments

overestimate social structures and do not leave enough space for alternative

types of actions and thinking. This results in mechanistic and static models

of society. But society is a complex system, it evolves dynamically and does

not depend upon mechanistic causality. Politics and culture influence economics

in various types of feedback processes.

3

Social Self-Organisation

Social

co-operation can be seen as a social relationship in which the mutual references

of the involved individuals (these are social interactions) enable all of

them to benefit from the situation. By co-operating, individuals can reach

goals they would not be able to reach alone. New qualities of a social system

can emerge by social co-operation. The elements, i.e. indi-viduals of this

system are conscious of these structures which can not be ascribed to single

elements, but to the social whole which relates the individuals. Such qualities

are constituted in a collective process by all individuals that are effected

and they are emergent qualities of social systems.Social

competition can bee seen as a social relationship in which the social interactions

as well as the existing relationships of power and domination enable some

individuals or social sub-systems to take advantage of others. The first benefit

at the expense of the latter who have to deal with disadvantages that arise

from the situation. New qualities of a social system can emerge by social

competition. The elements/individuals of this system are conscious of these

structures which can not be ascribed to single elements, but to the social

whole which relates the individuals. But these qualities are not constituted

collectively by all concerned individuals, they are constituted by subsystems

of the relevant system that have more power than others, dominate others or

can make use of advantages that derive from higher positions in existing social

hierarchies. These qualities reflect relations of domination in social systems.Social

information can have a co-operative or a competitive character. This depends

on the way of its constitution and the structure of society. If social information

is established by interrelated references of all individuals who are effected

by its application and if each involved individual has the same possibilities

and means of influencing the resulting information structures in his/her own

sense and purpose, the resulting macroscopic structure is a form of co-operative

social information. This type of information is collectively established by

co-operation of the involved actors as an emergent quality of a social system

in a process of social self-organisation (II). We call this

form of social information inclusive social information. Here social

self-organisation (II) denotes that the individuals effected by the

emerging structures determine and design the occurrence, form, course and

result of this process all by themselves. They establish macroscopic structures

by microscopic interrelations. If

social information is not constituted in processes of co-operation by all

individuals that are effected, but by a hierarchic subsystem that has more

power than other subsystems, dominates others or can make use of advantages

that derive from higher positions in existing social hierarchies, the resulting

structures are types of qualities that result from social competition – in

this case we speak of exclusive social information. Exclusive social information

is a new, emergent quality of a social system. It is constituted by social

competition and reflects relationships of domination and the asymmetric distribution

of power in the relevant social system. We can not say that exclusive social

information is established in a process of social self-organisation because

not all concerned individuals can participate in this process and can influence

it in the same way using equally distributed resources and means.

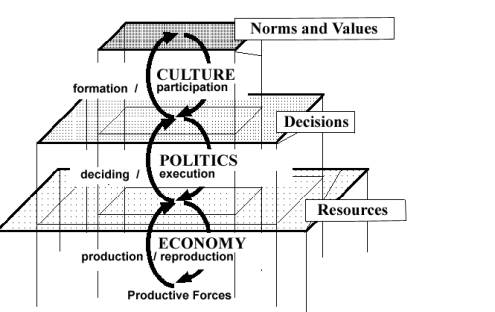

Figure 2: The dialectical relationship of individual and social

information

Considering

the self-organisation (I) (=re-creation) of social systems, it can be said that

by relating actions and hence individual consciousness of subjects socially,

social information emerges. Social information can be seen as a type of social

consciousness that emerges from the social relation of the individual consciousness

of participating subjects in a social situation. A social system organises itself

permanently in order to maintain itself and it permanently produces and changes

social information. As shown in figure 2 this is a dialectical process: Social

information emerges from individual information. The subjects of society create

and change social systems by relating their actions and hence their consciousness.

New patterns emerge from this process. On the other hand we have a process of

dominance: Individual consciousness can only exist on the foundation of social

processes and social information. Social information restricts and enables individual

consciousness and action. In this dialectical relationship of individual and

social information, we have the bottom-up-emergence of social information and

the top-down-emergence of individual information. On the macroscopic level of

the social system, new social information can emerge during the permanent self-organisation/re-creation

of the system. On the microscopic level, social information takes its effects

in a process of domination and new individual information can emerge. So domination

can be seen as a type of top-down-emergence. The endless movement of individual

and social information, i.e. the permanent emergence of new information in the

system, is a two-fold dialectical process of social self-organisation (I) that

makes it possible for a social system to maintain and reproduce itself.The

world system we live in depends on exclusive social information in the areas

of economy, politics and culture. So it can be said that it has a very low degree

of social self-organisation (II). The exclusive character of social information

is related to general antagonisms of society. An alternative would be a social

systems-design [see Banathy, 1996] that relies on co-operation instead of competition

in all social areas. This would include participative structures that guarantee

a high degree of autonomy for the individuals and enable them to fully participate

in reaching decisions that effect them. So such a social system relies on social

self-organisation (II) of all areas of society: the economy, politics, culture,

the workplace, friendships, personal relationships, education etc. Such an integrative

democracy as a self-organising, self-institutioning and inclusive society could

maybe overcome some of the shortcomings and problems that are produced by modern

society. Thus far we have not accomplished getting rid of the diverse manipulations

in society that trigger the domination of social competition and exclusive social

information in order to become self-determining, autonomous and altruistic individuals

that can choose and differentiate their individual and social information all

by themselves. “[We are facing] the threat of extinction of our species. Perception

of this tendency […] suggests an imperative of (literal) survival of our species,

namely unification of whole humanity, that is, replacing competition by cooperation

on all levels of organization. […] I conceive of a civil society as one in which

every “other” is seen a potential cooperator, not a competitor, nor an exploiter,

nor a boss, nor an underling, nor a customer” [Rapoport, 2001: 10+12]. “[All

of this] means that the role of competition should be progressively minimized

and replaced by cooperation. […] Frankly, this view goes against the present

triumphalist current of market economy orthodoxy” [Rapoport, 1998: 15].

References

[Artigiani, 1999]

Artigiani, Robert. Interaction,

Information and Meaning. In: Hofkirchner (Ed.) The Quest for A Unified Theory of

Information. Amsterdam.

Gordon & Breach. pp 477-488

[Banathy, 1996]

Banathy, Bela. Designing Social Systems in a

Changing World. New York, NY. Plenum.

[Ebeling and Feistel,

1992] Ebeling, Werner/Feistel, Rainer. Theory of Self-Organization and Evolution. The

Role of Entropy, Value and Information. In: Journal of Non-Equilibrium

Thermodynamics 1992, Vol 17, Iss 4. S.

303-332

[Ebeling, 1993]

Ebeling, Werner. Entropy

and Information in Processes of Self-Organization - Uncertainty and

Predictability. In:

Physica A 1993, Vol 194, Iss 1-4. S.

563-575

[Ebeling/Freund/Schweitzer,

1998] Ebeling, Werner/Freund, Jan A./Schweitzer, Frank. Komplexe Strukturen:

Entropie und Information. Stuttgart. Teubner.

[Engels, 1884] Engels,

Frederick. Origin of

the Family, Private Property, and the State. Marx/Engels Selected Works, Volume Three

[Fuchs,

2001] Fuchs, Christian. Social

Self-Organisation in Information-Societal Capitalism (in German, Soziale Selbstorganisation im

informationsgesellschaftlichen Kapitalismus). Wien/Norder-stedt. Libri BOD

[Fuchs,

2002] Fuchs, Christian. Aspects of Evolutionary Systems Theory in Economic

Theories of Crisis with Special Consideration of Socio-Technological Aspects. University

of Technology Vienna, 2002, forthcoming, dissertation, in German

[Fuchs and

Hofkirchner, 1999] Fuchs, Christian and Hofkirchner, Wolfgang. Information in Social Systems. Talk at the 7th International

Congress of the IASS/AIS, 10/04/1999. in Walter Schmietz (Ed), Sign

Processes in Complex Systems. Proceedings of the 7th International Congress of

the IASS-AIS. Dresden. Thelem.

ISBN 3-933592-21-6.

[Fuchs and

Hofkirchner, 2001] Fuchs, Christian and Hofkirchner, Wolfgang. Ein

einheitlicher Informationsbegriff für eine einheitliche

Informationswissenschaft, in Christiane Floyd, Christian Fuchs and Wolfgang

Hofkirchner (Ed), Stufen zur Informationsgesellschaft. Peter Lang

Verlag, 2001, forthcoming.

[Fuchs et al., 2001]

Fuchs, Christian/Hofkirchner, Wolfgang and Klauninger, Bert. The Dialectic of Bottom-Up and

Top-Down Emergence in Social Systems. Talk at the Conference „Problems of

Individual Emergence“. Amsterdam, NL. 04/16 - 04/20/2001 (publication forthcoming,

Systemica)

[Giddens

1997] Giddens, Anthony. Die

Konstitution der Gesellschaft.

Frankfurt/Main. Campus. 3. Auflage

[Goonatilake

1991] Goonatilake, Susantha. The Evolution of Information: Lineages in Gene,

Culture and Artefact. London.

Pinter.

[Gramsci, 1980]

Gramsci, Antonio. Zu Politik,

Geschichte und Kultur. Reclam

[Haken, 1988] Haken, Hermann. Information

and Self-organization: a macroscop. approach to complex systems. Berlin. Springer.

[Hofkirchner, 2000]

Hofkirchner, Wolfgang. Projekt Eine Welt. Oder: Kognition, Kooperation,

Kommunikation. Technische Universität Wien. Habilitation

[Küppers 1986]

Küppers, Bernd-Olaf. Der Ursprung

biologischer Information. München u.a. Piper

[Mainzer, 1998]

Mainzer, Klaus (Hrsg.). Information

- Interaction - Emergence. From Simplicity to Complexity. Braunschweig.

Vieweg.

[Marcuse, 1937]

Marcuse, Herbert. About

the Affirmative Character of Culture. In:

Kultur und Gesellschaft 1. Suhrkamp. (in German)

[Rapoport, 1998]

Rapoport, Anatol. The

Problems of Peace from a General Systems Theory Perspective. Paper presented at the 5th

European School of Systems Science. Neuchâtel, September 7th-11th,

1998

[Rapoport, 2001]

Rapoport, Anatol. Bertalanffy. Paper presented at the Bertalanffy

Anniversary Converence „Unity through Diversity“. Vienna, November 1st-4th,

2001

[Thompson,

1961] Thompson, Edward P. Review of Raymond Williams’ The Long Revolution.

In Jessica Munns and Gita Rajan, Gita (Ed), A Cultural Studies Reader. Longman,

1995. pp. 155-62

[Williams,

1961] Williams, Raymond. The Long Revolution. Chatto & Windus